Diterbitkan semula di bawah ini catatan sejarah hidup Prof. Dr. Khoo Kay Kim, “We were not an ordinary country”, dari the NUT GRAPH.

Daripada artikel tersebut, ingin di "highlight" maklumat-maklumat berikut:-

1. Mengenai salah seorang forefathers kita, Tun Tan Cheng Lock

[The British] could not bring the people together because people preferred to be separate. The British did not deliberately separate them. The British even set up a community liaison committee to bring the people together in 1949. Then MCA president, (Tun) Tan Cheng Lock, in his address to the party in 1949 chose the title “One Country, One People, One Government”. They tried really hard in those days to unite the people.

Daripada slogan "One Country, One People, One Government" yang sangat mirip kepada slogan perpaduan kita selama ini, "Satu Bangsa, Satu Negara, Satu Bahasa", adakah anda rasa Tun Tan Cheng Lock (bekas presiden MCA) menyeru ke arah membenarkan kewujudan sistem pendidikan vernakular yang "separate" dari sistem pendidikan kebangsaan? Cuba tanya DS Najib.

2. Jawapan Prof. Dr. Khoo apabila ditanya, "Are you hopeful for Malaysia’s future, then?"

For my generation, it is very disappointing. We were not an ordinary country. Unless the schools begin to do something now, [improvements] will not happen. It’s difficult to look into the future. One thing historians are not good at is telling what the future will be like.

"Unless the schools begin to do something now." No further comment. Tanyalah DS Najib.

Diterbitkan semula artikel penuh the NUT GRAPH di bawah ini.

“We were not an ordinary country”

By Deborah Loh | 17 October 2011 |

HAD history not intervened, Emeritus Prof Tan Sri Dr Khoo Kay Kim might have been a footballer. Of his youth, Khoo said he would have been content getting a simple job as long as he could have gone on playing soccer competitively even though there was no money in the sport back in the 1950s.

|

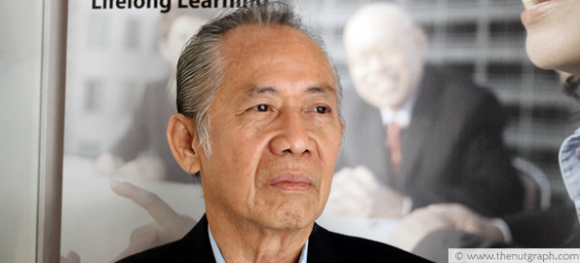

| [Khoo at his KDU University College office (all pics below courtesy of Khoo Kay Kim)] |

But Malaya’s independence happened, and uncertainty about the future made him opt for university instead. His obtained his undergraduate degree in history from University of Malaya in Singapore in 1959. His Masters and PhD were done at Universiti Malaya (UM) in Kuala Lumpur, where he began a career in academia. He started out as a tutor and rose through the ranks to become a history professor. He is now Emeritus Professor of the History Department at UM and also KDU University College chancellor.

When the bloody race riots of 1969 happened, Khoo was roped in, in the aftermath, to draft the Rukun Negara. Today, Khoo is one of Malaysia’s prominent national historians and is still frequently quoted in the media. He is also the father of poet, writer and art curator Eddin Khoo.

In an interview at his office at KDU University College in Petaling Jaya on 19 Aug 2011, the senior Khoo recounts the trepidation, instead of joy, that he felt as Malaya approached independence. And how, for his generation which has seen the best of Malaya and Malaysia, things are now “very disappointing”.

TNG: Where and when were you born?

Khoo Kay Kim: I was born in Kampar in 1937, when the Sino-Japanese War broke out.

|

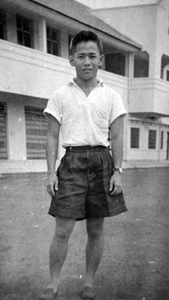

| (As a student at St Michael’s, Ipoh, in 1954) |

Is Kampar where you grew up?

I was born in Kampar because my mother went home to her father’s place to give birth. In those days, the women tended to go back to their own families; they felt safer than with their in-laws.

Also, my father was from a very rich family but by the 1930s there was an economic slump. However, my mother’s family was still very well-to-do. My maternal grandfather was a tin miner. He had two American cars before the war.

My father was a civil servant. My paternal great-grandfather was also a tin miner. Both he and my mother’s father were in the Kinta Valley. But both my parents were originally from Penang. The families moved to Perak for tin mining.

So where did you spend the most time growing up?

I spent my primary school days in Teluk Intan which used to be called Teluk Anson. I went to the Methodist Anglo-Chinese School (ACS) there until primary six. Classes in the morning were in English, and Chinese classes were in the afternoon.

What are your strongest memories of the place where you grew up?

We were so diverse and yet, so close. We grew up together without making serious distinctions among the races. I found that as I grew up, I had no communal feelings. And this is very important to me because when I work on Malaysian history, I can work on all three ethnic groups [that are predominant in the peninsula] unlike most [scholars] who would choose their own ethnic group.

What was so significant about your childhood that you felt this way?

My friends. My neighbours. My father was a government servant all his life so he stayed in government quarters. And they did not make distinctions there, which is why people who claim that the British practised divide and rule are talking rubbish. If the British did, they would have had one part of the government quarters meant for one particular ethnic group…they never did that. My neighbours were Malay, Indian and Eurasian [Malayans].

[The British] could not bring the people together because people preferred to be separate. The British did not deliberately separate them. The British even set up a community liaison committee to bring the people together in 1949. Then MCA president, (Tun) Tan Cheng Lock, in his address to the party in 1949 chose the title “One Country, One People, One Government”. They tried really hard in those days to unite the people.

I remember in late 1945, when the Japanese surrendered, there were ethnic clashes in [some] places. Teluk Anson was one of those places but our neighbourhood had no problem. The clashes occurred because for two weeks after the Japanese surrendered and before the British returned, the Communist Party (of Malaya) went around punishing people whom they accused of having worked with the Japanese. So when they did that to the Malays, the Malays retaliated. One Chinese could not be distinguished from the other, and because the majority of communists were Chinese, they (the Malays) felt that any Chinese could be one. But mostly, in many areas, despite the diverse population, there were no clashes.

|

| (With eldest son Eddin) |

Do you have any significant memories of childhood friends and what you did together?

Most of my friends were footballers, so I was one, too. I won my first football prize on 1 Feb 1949 for an inter-school division three game. In those days, all the schools encouraged sports, now it’s different. And teams were less racialised then.

A lot of Chinese [Malaysians] have stopped playing football. Those days, they were very active. One reason why the Chinese ended up playing ping pong and basketball was that many of the Chinese [vernacular] schools had no fields. Whereas government and mission schools always had fields. The British were very particular about encouraging sports. And there was not enough land for Chinese schools. The land was just sufficient to build a basketball or indoor court. So they were forced to concentrate on indoor games.

After primary school at ACS, did you stay on in Teluk Anson?

No, I went to Ipoh [for] secondary school at St Michael’s. (Tun Dr) Lim Keng Yaik was one year my junior. I really enjoyed those years although in Ipoh I was cut off from a lot of Malay friends. But I became very close to the Indian boys because of football. So a lot of my closest friends were Indians. I still had a lot of Chinese friends.

|

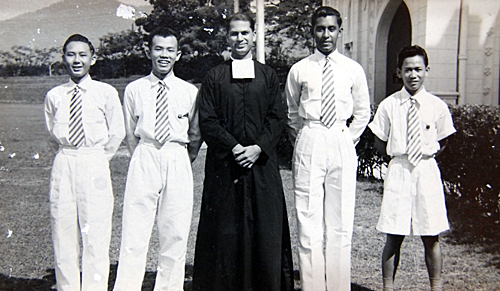

| (At school in St Michael’s, Ipoh in 1955. Khoo is last on the right) |

Can you trace your ancestry?

Back to China would be very difficult. I am about the sixth generation in Malaya. We can trace our ancestry back to the Khoo kongsi in Penang. My great-grandfather was one of the kongsi founders. I think before he went into tin mining, he was a cook.

What about your mother?

My mother’s father was a tin miner but he started off as a shop assistant. His father-in-law liked him very much because he was very hardworking, so he allowed him to marry his daughter. [My grandfather] then became a tin miner.

My mother’s side was richer than my father’s side when they were about to get married. As I’ve mentioned, my father’s family was affected by the 1930s economic slump. Hokkiens those days had this system whereby in a situation like that, the woman’s family would pay for the wedding. And in my father’s case, the celebration in Kampar lasted three months! They had the Chinese opera perform.

What was it like, transitioning from being first a Malayan to a Malaysian?

|

(Khoo with friend and colleague,

the late English Literature professor Lloyd Fernando,

on a hiking trip in the late 1960s)

|

We were very worried. The people of my generation had been quite used to the British administration. By the 1930s, Britain had already shaped up the country and we were doing very well and then the war came, unfortunately. After the war, countries across Asia began talking about freeing themselves from colonial rule, so [Malaya] also followed suit.

But the English-educated were very worried. They were not sure what would happen. They read about India and Gandhi’s assassination, they read about the resistance movements against the Dutch in Indonesia. America was of course very quick to lead, hoping to set the example — they freed the Philippines by 1946.

So on Merdeka Day, what do you remember feeling?

I was with a group of older people, feeling uncertain about what the future would be like. We could not predict [anything] but we were preparing ourselves. That’s when I decided I would go to university because the talk was that we would need to take over the positions vacated by the British. So we felt that we should study hard and obtain high qualifications so that we could fit into these jobs.

Otherwise, I had wanted to be a footballer. Footballers in those days would get a job as a clerk, and stay with their parents and get pocket money. It was not a professional sport and as much as my friends and I loved it, we also realised that it had no real future.

When I decided that I wanted to go to university, my father didn’t really have enough money to send me. But my luck was such that at that point in time, he had a promotion.

And so you embarked on your path as an academician and historian.

|

| (Khoo married N Rathimalar in 1966) |

I was appointed lecturer at UM after two years of tutorship in 1967. I was already good in Bahasa Malaysia. By the way, I learnt to speak Malay on my own. It wasn’t taught when I was in primary school. I happened to take a great liking to P Ramlee and got hold of all his movies and songs. That’s how I taught myself Malay.

[At UM] I could hold tutorials in Malay, and I was the first non-Malay to lecture in Malay. I was unusual in that sense. So I became very close to the Malay students. Once or twice I was called upon to settle problems caused by [chuckles] Anwar Ibrahim [who] was very much a nationalist when he was a student. One day, he and his friends painted all the English signboards on campus red.

How did you get roped into co-authoring the Rukun Negara?

It was [Tun] Ghazalie Shafie’s idea. He was inspired by Indonesia’s Pancasila. There was a panel of us who were from all walks of life. Ghazalie put the idea to this panel [which] discussed [a] draft and recommended it to the National Operations Council.

What was the process of drafting the Rukun Negara like?

The panel members got along very well with one another. The elements of the Rukun Negara were given to us; we mainly put it in words. On the first principle, “Kepercayaan Kepada Tuhan”, we debated whether somebody who wanted to be an atheist would be allowed to do so or if the law would descend on him [or her]. We felt that this was not likely to be a crisis because in Malaysia, most people had a religion. And sure enough, when the whole thing was announced, there was no opposition. And if a handful of people want to be atheist, so what?

How do you feel about the Rukun Negara as it is applied today?

|

| (Graduation from University of Malaya in Singapore in 1959) |

The unfortunate thing is that it was never properly explained to school children. The education system is only concerned with exams and giving the right (textbook) answers.

Look at a lot of places, for example, UM. Students of various ethnic groups are not close. Even the lecturers are not close. [...] People are uncomfortable with one another because they don’t really understand other people’s culture and religion. We can only reverse this by starting all over again at the school level.

Are you hopeful for Malaysia’s future, then?

In the early 1950s, when we were still part of the British Empire, our contribution to Britain in terms of revenue was the highest from the region. In early 1949, our badminton players went to London and they brought home the Thomas Cup. These players dominated badminton at the world level for so many years. Back then, our badminton players went to China to teach them how to play. Now we have to get coaches from China. In 1950, our weightlifters won two gold medals, one silver and one bronze at the British Empire Games in Auckland. We invented sepak takraw. Now we can’t even beat Korea or Thailand.

For my generation, it is very disappointing. We were not an ordinary country. Unless the schools begin to do something now, [improvements] will not happen. It’s difficult to look into the future. One thing historians are not good at is telling what the future will be like.